Note to Readers

If you are joining from the Wordpress blog, thanks for making the move to Substack with me! I’ve found the tools on Substack may offer new ways to be in community together! I invite you to subscribe to take full advantage of these tools and receive each new post delivered to your inbox!

Introduction: “What Should Dad Write About?”

“Boys, you know that we had that brain cake to recognize my seven year ‘cranniversary’ for my craniotomy (surgery) and living with brain cancer? What should dad write about on his blog for this big milestone?”

We talked over lunch, and Isaac (our oldest; 11 years old) said, “It’s awesome that you’re still alive! Tell people that.”

Good one!

Gideon (our youngest; 7 years old): “Maybe that you’re getting a pet chicken?”

We are, in fact, not getting a pet chicken.

Noah (our middle guy; 9 years old) looks down at his pizza lunchable, then up at me, “Tell people how to live with brain cancer!”

There it is!

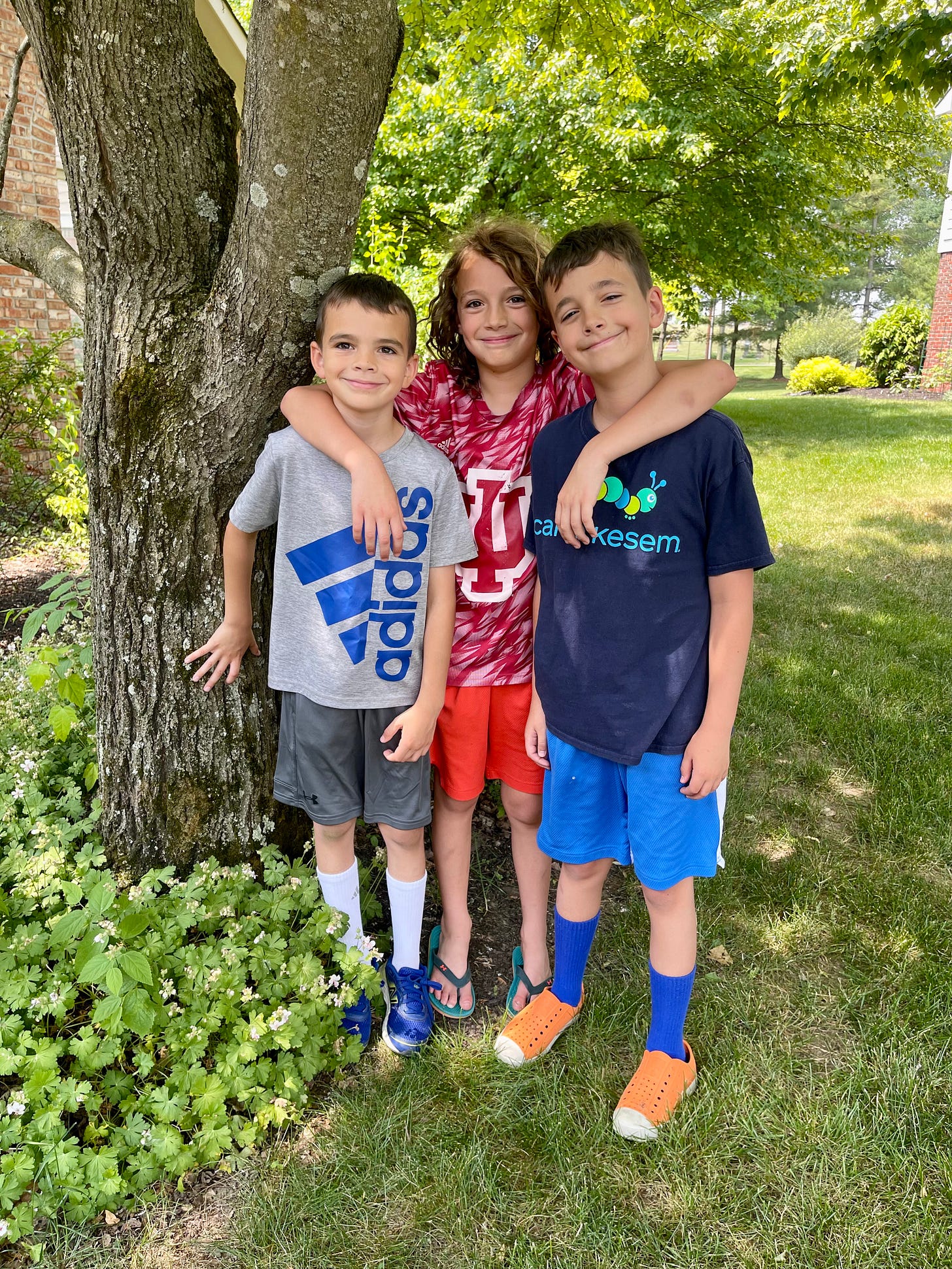

And so, brought to you by the #HaydenHooligans, after seven years, here is my post responding to the prompt: How to live with brain cancer. Sort of. There’s a lot that I didn’t mention, but these thoughts were those that felt most pressing as I sat down to the keyboard today. I can promise you that more posts are coming in fairly rapid succession! I want to share a few advocacy highlights and a new tool to support the community in forthcoming posts.

In this post I talk about MRIs, mental health, and survivorship.

What Do You Mean by Stable?

“Live by the scan; die by the scan. MRIs are central to the lived experience of brain cancer,” I tweeted on May 29, 2023, with a link to a peer-reviewed paper about the experience of interval MRI scans for disease surveillance in people living with malignant brain tumors.

The MRI scan is a sort of sacred ritual for brain tumor patients; sacred in the Kierkegaardian sense of Fear and Trembling that Kierkegaard wrote to better understand the anxiety that the Biblical character Abraham may have felt on the way to sacrifice his first-born, Isaac. Now I’m not here to remark on this story (at least not in this post, but I do have a Substack where I discuss religious studies!)

Channeling Kierkegaard, anxiety over deep uncertainty is an accurate description for routine MRI scans. We, patients and care partners, refer to the unsettling feeling before scans as scanxiety (scan + anxiety). And the routine scheduling and protocols for the imaging procedure do bear striking resemblance to something holy! You wear special clothing (the hospital gown), experience your body pierced with an IV needle, sacrifice yourself to the humming, beating, beeping machine for an hour, and contemplate your mortal future.

Whitney and I created our own ritual to prepare us for these anxious days: The MRI Scan Day Selfie. We’ve been taking these since the beginning! Literally. Here is one of the earliest treatment related selfies I turned up. This one from June 28, 2016, about a month after surgery, during the daily chemo and radiation portion of the standard of care protocol.

And following are some more recent snaps from this year. Checkout the scan day selfie in the lower right!

The hoped-for outcome for MRI scans is worded like, “No evidence of disease progression,” or, “residual tumor unchanged from comparison with prior scans.” This is what we mean by a “stable” scan. As much as we try to explain this, it is difficult for those outside of the brain tumor community to appreciate that just about the best news you can get is that your cancer isn’t growing. Words like “disease free” and “remission” are not used in our community, especially for malignant brain tumors. You never “cure” a malignant brain tumor. This isn’t pessimism, it’s pragmatism!

Establish rituals to ground yourself in the familiar and wrap yourself in the comfort of routine.

We celebrate stable scans, and for my next scan, we scheduled five months out from my previous scan, and this is more reason to celebrate! Five months is the longest duration I’ve gone between MRIs. This is a huge relief to get a few more weeks between scans, and we’re so happy.

The truth is, friends, I’ve had nearly 40 scans in seven years, and the emotional ride of anxiety and relief, every three or four months, is exhausting. There may be stable disease on MRI, but a stable emotional state is something else. I am really struggling to maintain my usual positive energy. I notice that my mood is more volatile, and my anxiety approaching our most recent scan at the beginning of this month was elevated more than usual.

I opened today’s post with these comments about MRIs because it’s a perfect example of long term cancer survivorship: You’re never far from your next scan and your next bout with the existential maturity that serious illness demands.

How to live with brain cancer: MRI scans: Establish rituals to ground yourself in the familiar and wrap yourself in the comfort of routine. Don’t be afraid to name MRIs for the anxious events that they are, and don’t forget that imaging is only one measure of health.

Mental Health: Values Consistent Living (Work in Progress)

Note: For this section about mental health, please do speak with your care team about appropriate mental health interventions. I am sharing my experience, and I hope it is useful to learn about, but it should be mentioned that I am not qualified to offer medical advice! Please speak with a clinician or otherwise certified mental health professional to navigate your own care! If you are in crisis, help is available to you: 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, or ACT, is a form of cognitive behavioral therapy where, “Clients learn to stop avoiding, denying, and struggling with their inner emotions and, instead, accept that these deeper feelings are appropriate responses to certain situations that should not prevent them from moving forward in their lives” (Psychology Today).

My mental health clinician practices this form of therapy, and the therapeutic benefit in my life has been significant. Happiness is elusive; is a nebulous thing to do define; is a squishy goal to pursue; is not always the way we “should be feeling.” So forget happiness! I say that with a smirk, but I mean it!

Instead, pursue psychological flexibility that “encompasses emotional openness and the ability to adapt your thoughts and behaviors to better align with your values and goals” (ibid.) This effort to live consistently with my values restores some agency and is empowering when the uncertainty and distress of living with impairments and the weight of serious illness leaves me feeling paralyzed.

Some of my values include: family and friends, self-knowledge, rationality, creativity, intimacy, purpose, humor, and achievement. For each value, I check in routinely to compare investment of energy to how I’ve ranked the priority of each value. For example, if a value is ranked in my top three, but my investment in living consistently with that value is low, then I’ll experience the discomfort of living out of sync with my values, and I can make a correction.

A big lesson here is that the investment calculus goes both ways. What I mean by this is that we don’t always identify under-investment of time for important values, we also identify over-investment for lower priority values. This presents an opportunity to refocus and re-align.

A good example for me is that achievement value. Yes, this value is important to me, it’s in my top 10, but not at the top, and yet, I invest loads of time and energy leaning into my desire for achievement. Selection for speaking events, getting an article published, being chosen for this or that professional appointment… each of these achievements matter to me, and I am damned proud of the way I have taken a devastating diagnosis and wrestled it into a net positive in my life. The hard truth is that I invest way more time in my day-to-day life in pursuit of achievements, when that particular value is ranked 8th place on my list.

I’m under investing in intimacy. That’s a vulnerable admission! Imagine how more values-aligned I would live my life if I were to take some of that achievement investment and refocus on intimacy? This is the power of this model of mental health care. I can rely on this general rubric or framework to make principled changes in my life to pursue values-consistent living. Have I figured all this out? Of course not. I’m a dumpster fire many days of the week! But grounding my activities in values and investment of time, I do not feel as paralyzed by distressing feelings, and I can make reasonable changes to align with what matters to me.

How to live with brain cancer: Values consistent living: I genuinely believe that each and every person can benefit from a therapeutic partnership with a mental health professional. Consider what theory of practice or delivery model your would-be therapist practices, and discern if that model will contribute to you meeting your mental health goals. Here, I have offered my experience with the ACT model of care.

Time: What to Do, If We Don’t Have as Much

I’ve written at length about mortality. I’ve also spoken quite a lot about it. More than two years ago I wrote this, appearing in a syndicated blog post at Cancer Health:

How are we going to live more years like this?“ Whitney asked me around our fourth ”cranniversary" (the anniversary of my craniotomy, the surgical procedure to remove my brain tumor).

I shared in that blog post:

“I’m not dead, and that’s weird, but I can’t say that publicly, without also putting in a lot of effort to unpack those words so that they don’t alienate others.”

The stress of uncertainty, the challenge of daily life with impairments, the fear that I’ll have a seizure when I’m home alone, and the drive to achieve, in tension with the presence our boys deserve from their dad are a few of the many competing priorities and daily realities of living with brain cancer.

Our family has a pronounced sense of time. We count days by pill box refills, months by long term disability payments, quarters by MRI scans, and years by brain cakes.

These are the reasons that Whitney asked then, and the sentiment holds, “How do we live more years like this?” It’s also the reason that I think it’s weird that I’m not dead yet. It’s the reason that when I prompted the boys for topic ideas for this blog post, Isaac’s reply was, “You’re still alive.”

Our family has an augmented sense of time. We count days by pill box refills, months by long term disability payments, quarters by MRI scans, and years by brain cakes. The accommodations that patients and loved ones are extended in the month or two after diagnosis, even the first year of active treatment, including meals, surprise visits, cards in the mail, extra flexibility at work, and bear hugs from fiends are more or less exhausted by year seven. Hell, we’re exhausted. This is not to signal to our community that we feel unsupported—just the opposite is true!

But cancer survivorship isn’t a protected class. If not suffering from debilitating impairment, the expectation is that you’ll continue fulfilling societal norms. Now for many, work brings them purpose, and so it is good to do that which brings meaning and purpose, but as disease fatigue sets in, when you could use that newly diagnosed support, the assumption is that your need for support is less, not more.

There is a lot that many cancer survivors can do, but is it appropriate that our norms suggest, thereby, there is a lot that we should do? This is where I derive the title for this section: What to do, if we don’t have as much time?

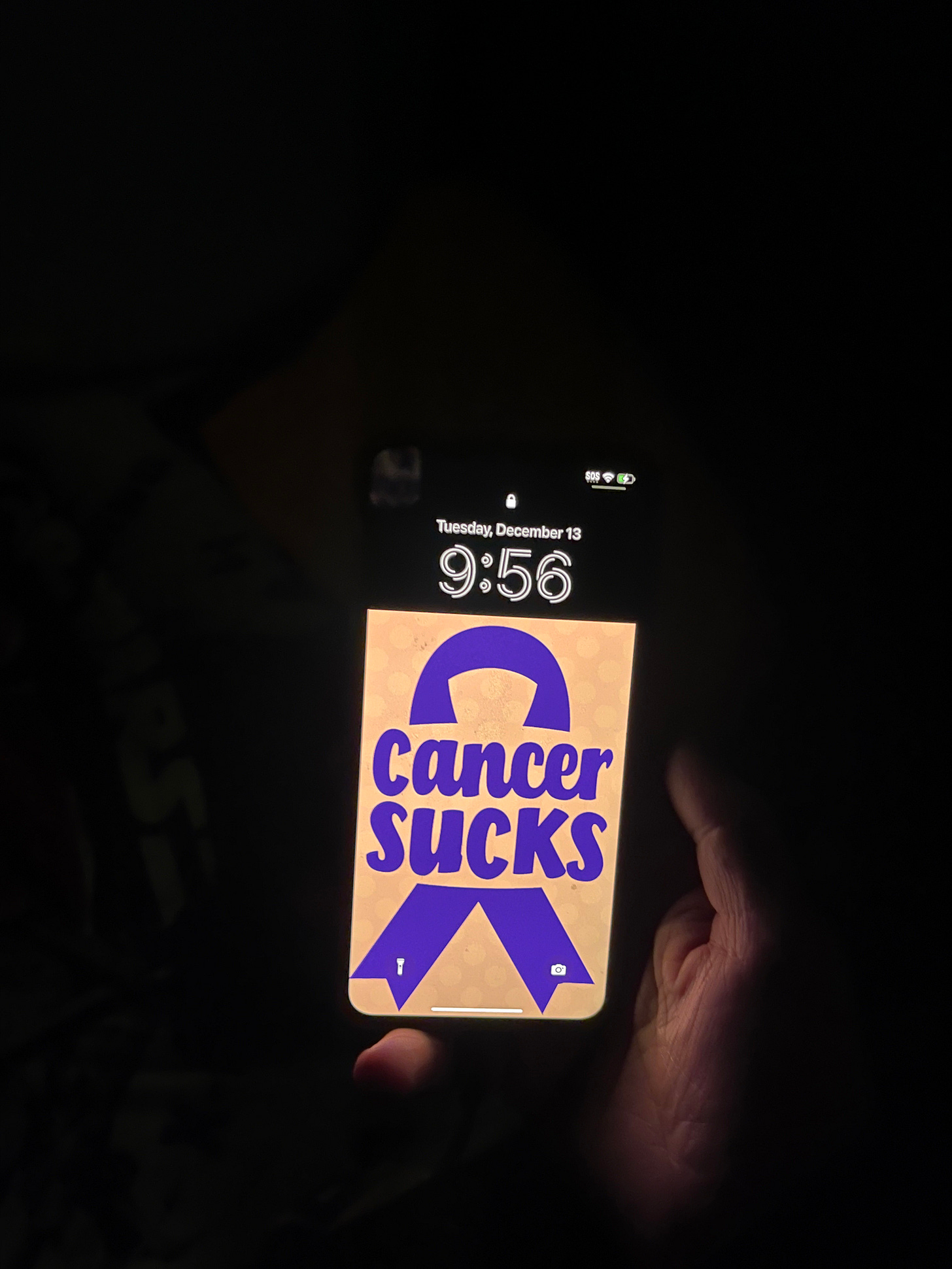

I think about this with our kids a lot. I was making my rounds tucking in the kids to be sure they were comfortable and warm before I went to bed, when I noticed Isaac’s wallpaper on the old iPhone we let him use: Cancer Sucks, the wallpaper stated with a ribbon. It struck me in that moment that we hold him accountable to school bus rides, homework, keeping his room clean, and all that, just like any other kid his age, but “any other kid” doesn’t have a dad with brain cancer, who has seizures, walks with a cane, doesn’t drive, and is statistically likely to die before many of his friends’ parents.

This is what I mean. Our family rallies around the slogan, “We can do hard things,” but how might we question that slogan if it instead said, “We should do hard things”?

Should we? People tell me that our kids will be “strong” for “overcoming adversity.” Friends, I’ll tell you, I’d take our kids soft and untested. I know some would disagree, but tell me if you think our 11 year old should go to bed with cancer on his mind?

Survivorship gets harder the longer you live it, and, paradoxically, sharing how difficult life is—just talking about, I mean—gets harder, too, because Whitney and I have so many friends who have died from brain cancer, while I keep on living, it’s hard to complain about distress when you’re still here, playing with the kids, cooking dinner.

How to live with brain cancer: The clock is ticking: Be present, be open, be honest, check on your friends with cancer, even if it’s been a few years after diagnosis, and careful how you reward “strength”—just because we can do hard things doesn’t mean we should.

Cheers and Beers for Seven Years!

Our neighbors surprised me with a handmade sign and a mixer of seven beers for seven years. Now that’s the sort of levity we need in this world! To all my friends, family, faithful readers, and those willing to make the move to Substack, this one’s for you! Stay tuned because I wasn’t able to cover all the material I had hoped to in this post, but hey, maybe I’ll have another seven years to get all that out!