I'm not Dead, and That's Weird

Patients are told not to throw in the towel, don't lose hope, hold out for the miracle, but when we frame cancer survivorship by a relentless battle, we award the wrong priorities. Instead we should celebrate reconciling the plans that we had for our live

"How are we going to live four more years like this?" Whitney asked me around our fourth "cranniversary" (the anniversary of my craniotomy, the surgical procedure to remove my brain tumor).

I shrugged. How will we?

My surgery occurred on May 26, 2016, and my official date of diagnosis was a couple weeks later, on June 10. Now that the calendar year has turned over, we see my five-year mark approaching on the horizon. (Expect another, likely more reflective post then!) By the population statistics, less than 10% of glioblastoma patients live to see this milestone. My radiation oncologist who congratulated me on becoming a long-term survivor at my 18 month follow-up would no doubt be surprised to see not only that I'm still kicking, but that I maintain part-time work and a pretty robust writing and speaking schedule. But Whitney was right: How do we live another four or five years like this?

The Brain Tumor Social Media (#BTSM; @BTSMChat) organizing team met for our quarterly meeting this past weekend. We gather every few months to brainstorm topics for the following monthly Twitter chats. Each meeting begins with an informal check-in, "the feels." Our team has grown over the years, and these days our members include four brain tumor patients, a former caregiver to a late spouse, and a neuro-oncologist. Together, the seven of us represent pretty diverse perspectives, yet we traverse shoulder-to-shoulder across the same common ground, rocky and turbulent as that ground is. Many of us lead support groups, are involved in patient care, mentor and assist newly diagnosed patients and their loved ones, and deliver talks and lectures. We are each other's support in many important ways, and our meetings, plus our group text thread, serve as the vehicles to say the honest things that we may not say publicly.

I'm not dead, and that's weird, but I can't say that publicly, without also putting in a lot of effort to unpack those words so that they don't alienate others.

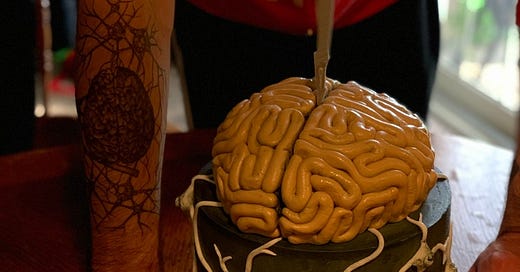

Adam during the #BTSM quarterly meeting in January 2021

Brain tumors and cancer are devastating. This maybe goes without saying, but often things that are so obvious are assumed to have shared meaning, and so we don't tug those stubborn details into the light to discuss them.

All cancer is bad, and there is no such thing as a "good" brain tumor, we often say in the brain tumor community. There are layers of nuanced meaning packed into the brain tumor experience. Some people are given a prognosis of 10, 15, even 20 years; others hear that they may only expect a year and a half. Prognosis is a statistical analysis based on tumor size, placement in the brain, molecular, or genomic, characteristics, and a host of other confounding factors. When it comes to outcomes, the ranges of survival are every bit as confusing, if not more so. Now, with only months until my fifth anniversary, I've sadly watched many friends die from their brain tumors, and yet here I am, blogging away, co-moderating Tweet Chats, wrestling with our kids, and masking up to grab a couple beers with friends when able.

The truth is, brain tumors are more than just aggressive cancers, they present an existential threat. Seizures and headaches, fatigue, my sensorimotor impairment that requires the use of a cane anytime that I'm out for more than just a few paces here and there, from the front door to the mailbox or the parking lot to a building entrance. I am beginning to notice more short-term memory loss, and I've grown more irritable and impatient, either that's me or the meds. Others face many more significant impairments than I've listed here: language processing issues, cognitive decline, near complete memory loss, and confusion.

The worse the symptoms are for others, the more distress creeps in, I think, "What's in store for me?" And when friends die, "How long have I got?" These are probably the obvious difficulties of living with serious illness. The more insidious stuff is the bewilderment of life. I'm not dead! And that is weird! But it's also a secret that I keep to myself.

Newly diagnosed patients and their loved ones have come to trust my voice, and others like mine, and the last thing we are looking for on the start of a journey is someone telegraphing from miles ahead, reporting that the path is treacherous. For our closest loved ones, the caregivers, they know our truths, and we know theirs, though they do not always align.

How will we live four more years like this?

But as those concentric circles expand, those other loved ones who are involved with our care but not the daily grind, and further in the ripples of our impact, extended family and social media followers, maintaining a positive outlook, giving hope and inspiration, calling for and expecting thoughts and prayers, these are the roles we play and anything less is threatening to the narrative that society has constructed around illness.

The rally cry is to fight, to battle, to be a warrior. "Do not go silently into that good night!"

We learned nearly five years ago that I could expect a year and a half. A doctor who oversaw the course of my radiation congratulated me on long-term survival at my third six-month follow-up: 18 months (we meet much more frequently with my oncologist). "I hope to see you again in another six months!" I exclaimed at the conclusion of that visit. "All we can do is hope," he replied.

This isn't a narrow miss or a near-death experience. This is one long, protracted journey toward the completion of my life, and rather than create safe spaces to interrogate the reality of our mortality, build out an infrastructure of care that places physicians, social workers, chaplains, and patients together to discuss end of life goals as a standard approach to care, or legislate social services solutions to free patients and loved ones from onerous disability paperwork and guarantee financial security from the onset of serious illness to the completion of life, no instead of that, we place the preparation of advanced care planning, disability application, and financial planning squarely on the shoulders of patients and their caregivers and loved ones.

Patients are told not to throw in the towel, don't lose hope, hold out for the miracle, but when we frame cancer survivorship by a relentless battle, we award the wrong priorities. Instead, we should celebrate reconciling the plans that we had for our lives with the reality that we may need to adjust our goals. We need to turn our attention toward grieving the life that is not. Maybe the miracle is not the life saving treatment breakthrough, but instead, it is the breakthrough of fresh perspective that asks honestly, "How would I like the completion of my life to look?" And not, "What I can possibly do to extend it?"

In the first couple of years after diagnosis the goal is survival. Recover from surgery, tolerate chemotherapy, arrange transportation for daily radiation therapy, and accept a life-limiting illness. But if we survive the first several months or a year of acute treatment, we learn that all the protocols are only to do that: facilitate survival.

Survival isn't living; survival is not dying. Life is agency, being responsible for one's own outcome, life is security and safety, life is space to explore living with illness, quality of life is answering the question posed by psychiatrist Jonathan Adler, "What does life mean to the person who's living it?"

I'm not dead, and that's weird, so by my own definition, I'm surviving, but I'm in the pursuit of answering that question about life's quality.

How do we live another four or five years like this? The truth is, I have no idea. You never put much thought into the first three or four years because you've been told that you'd be lucky to get that many. But having reached this provisional place of surprising survival, I suspect the answer lies somewhere in systems changes so that we can get in place better structures to support patients with terminal diagnoses. Beyond that, I think it's important that we normalize these questions and begin to reward authentic confrontation with mortality.

I'd rather leave a legacy of wisdom than war.